Teaching Philosophy

“I hope that I say something that unsettles you.” This was the opening statement of Dr. Cornel West’s lecture during his visit to my alma mater, Metropolitan State University of Denver in 2014. Although he was determined to unsettle those of us in his audience, he spoke with care and compassion. I’ve developed my teaching philosophy around unsettlement because gaining knowledge requires confronting the unknown and the unfamiliar with curiosity and an open mind.

My classroom practice begins with defamiliarization, a process that allows us to return to minor details and reintroduce ourselves to the world, systems, habits, and relationships to which we have grown overly accustomed. Defamiliarization encourages us to slow down and shed our assumptions. I begin each class with freewriting where we acknowledge those frustrating words stuck on the tips of our tongues, or see how far our minds can wander when meditating on single adjectives or the chaos in a Hieronymus Bosch painting. In teaching rhetoric and composition, an emphasis is placed on building strong arguments and synthesizing information, which are positive, necessary skills, but they tend to overshadow the equally important, though difficult skill of asking questions. Naturally, defamiliarization sets us up to ask questions, even when orbiting the seemingly obvious, and even in a world overly saturated with data and search engines at our fingertips.

Defamiliarization may segue into growing pains. Higher education is an emergent moment in the lives of students. Rather than hold each student to a single standard, my assessments are rooted in self-reflections which measure their growth, their reception to feedback, their contributions, and their ability to identify their own strengths and weaknesses. Additionally, I learn a lot from the student’s reflections—this metacognitive approach reveals thoughtful and creative insights about different learning processes, giving me the opportunity to turn individual weaknesses into collective learning outcomes.

Trust and transparency are elements of my classroom practice that I continue to strive towards, both for students and for myself. Having always been a committed and curious student, thought not necessarily a perfect one, I draw on my own academic struggles to effectively reach students regardless of their learning style or comprehension levels. This perspective allows me to meet students where they are and to normalize honest self-reflection in the classroom. All of this shapes my third tenet: recognition. A major part of higher education is establishing ethos. In doing so, I remind students of the responsibility and privilege that comes with being a scholar. Who are we doing it for? I hope to build an ethical framework in the classroom, foregrounding collective growth and recognition rather than individual mastery alone.

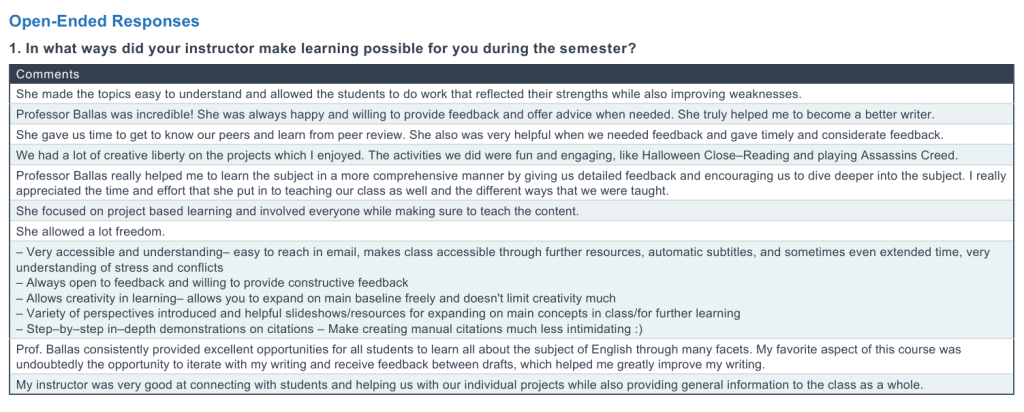

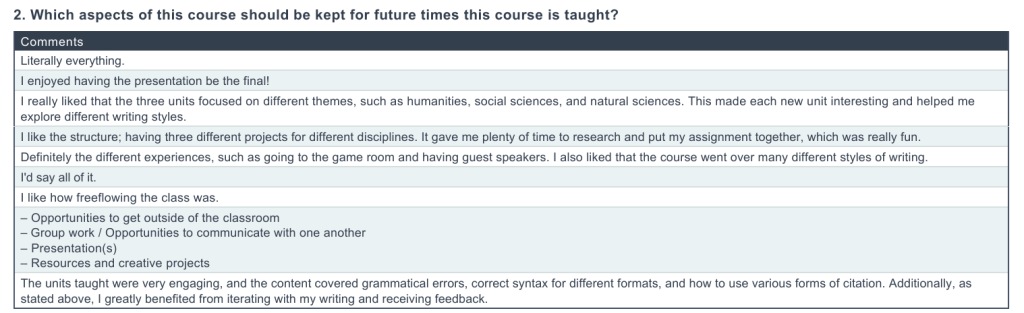

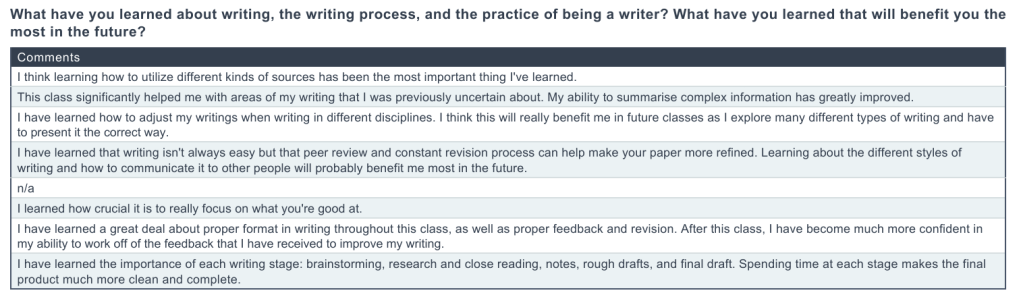

Student Evaluations

Teaching Observation:

Notable Strengths:

Gave detailed explanations of assignment parameters

Checked in with the class frequently to gauge understanding

Had good rapport with students/they seemed comfortable asking the instructor questions and engaging in discussion

Goals to Work Towards:

Time management: Will streamline grading process

Building student example repository: Instructor will begin saving best student work for future use as student examples

Strengthening Relevance of Units to Real-world Genres: Instructor expressed interest in incorporating critical theories into student activities